Photo taken from Reddit (/u/iemwanofit)

Photo taken from Reddit (/u/iemwanofit)

The sisig question

As a Kapampangan, I often get asked about my thoughts on sisig—would I like it with mayonnaise; with egg; or even served sizzling, on a hot plate? To give you the short answer: I honestly don’t care, as long as it tastes good.

Saying that may draw the ire of a big number of kabalens who hold very strong views on what “true” sisig is.

Edward Lusung, owner of the famous Conching restaurant in Guagua in lower Pampanga, exclusively served this type of sisig but the huge demand for the grilled version made him decide to serve both versions.

But acceptable innovation ends there. Says [Edward] Lusung, “Egg and mayonnaise is a big no! This is a shortcut and [a disrespect for old school Kampampangan cooking]. I was taught by my grandfather and grandmother how to cook it religiously”.

Angeles tourism officer Joy Cruz agrees. “It’s a total disrespect because perfecting the sisig to have its authentic taste [and chewy texture] is something you earn from experience and acknowledging the history of how it evolved from the Kapampangan sensibilities as a heirloom recipe,” she said.1

While I’m not an authoritative source (and I might argue, no one should be, in terms of food, anywhere), I can tell you about the sisig I knew, the dish I grew up with, which my dad makes:

- He would buy crispy ulo (head of pig), along with some offal (liver, heart)

- Chopped them up, and in a bowl, mix in calamansi juice and red chilis

- Serve as-is, at room temperature It wasn’t sizzling. Yes, it was chewy (and creamy, thanks to the liver). No eggs or mayonnaise. No butter. But I’d still enjoy a dish of buttered, egged, mayo-ed “Manileño sisig” the same way.

What even is “true” sisig?

The sisig mythos

- There are written records of the word “sisig” back in the 1700s where it was used to describe a dish akin to a salad today: said to include green guava or green papaya with vinegar and spices2.

- It then evolved to a form where meat dominated the dish, but the meat is instead boiled, still made sour and spiced.

- There’s also a story where discarded meat (pig’s head, offal) from American soldiers in Clark is used.

- Finally, the form that is said to be the “authentic,” modern sisig is “conceived” when Aling Lucing (whose death has a rather dark, gruesome side—do read up on it) started grilling the meat first.

This rough chain of stories dominate the Kapampangan psyche today, including me. I’ve heard these stories in my childhood—predating the (arguably baseless3) Wikipedia citations on the sisig page today. However, I do believe there are some nuances to be considered.

- We’re considering only the written record. Note that Bergaño was a friar and literate—when most non clergymen weren’t. Sadly his is the only written record we have, and we can definitively base off the use of the word “sisig” only from his accounts. Scribing had to be economical back then, so the account may have also missed important regional details (much like the differences we have today). We may never know for sure (1) how long we’ve been making “sisig” and (2) if meat was already being used by then—not only in guava or papaya form.

- The Clark origin story, while convenient, may also be untrue. First, cooking with offal is already commonplace in Philippine cuisine (e.g. kilawin, dinakdakan, papaitan), let alone pig’s head. You’d think there would also be multiple accounts by then, similar to Korea’s budae-jjigae. Once again, we may never know if this is the case, unless we’d have some actual written sources pop up in the future.

- Aling Lucing, I believe, is only given credit for the purposes of publicity. Saying you’re the first to grill the meat for a dish like sisig is a very bold claim. I’d say it’s not far off some random person already regularly made grilled/crispy sisig way before the mid-1900s. Sadly, this claim is uncontested, not unlike the other claims.

Interpreting sisig

So where do you draw the line? Is there a need to delve into Platonic ideals and distill down sisig to its “perfect Form?” From me to you, “true” sisig does indeed exist, but it’s different for everyone. It’s subjective. It’s also ever-changing. A little thought experiment: if you’d put a 1700s Kapampangan man into a time machine and brought him to Aling Lucing’s, what face will they make when you make them eat sisig? Will they exclaim blasphemy? Will they have a Damascus moment? Show indifference?

Personally, if I’m being pedantic, I define sisig as a cooked dish with chopped ingredients that is made mostly sour. Of course, I wouldn’t be absurd enough to call sinigang, sisig (since it isn’t chopped up), or pad kra pao gai, sisig (since it isn’t mostly sour). I typically attribute it to the etymology of “sisig,” which means to make sour, in Kapampangan. There’s a theory that “sigang” (sinigang) may be adjacent to this definition, but I’m unable to find reliable sources there as well—though it’s nice if that’s true.

I’d also like to add that I’m not about to commit a social faux pas by exclaiming “this isn’t sisig!” if someone serves me a plate of mostly salty, savory, eggy sisig. I’d still harbor thoughts in silence in the lines of: “this isn’t sour enough.” And unless the cook’s a friend, I’d rather not kapampangansplain the origins of sisig and tell them how we make sisig at home. Hey, if it’s good food, it’s good food, whatever chef wants to call that dish.

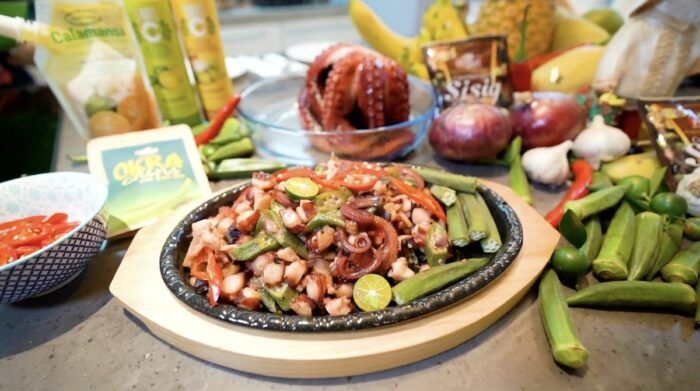

I’ve also tried many other variants, such as octopus sisig pictured above. While I try to avoid eating octopus if possible (due to their likely sentience), I wouldn’t refuse it. I’ve had the privilege to try out octopus sisig when Mama Sita’s Sisig Mix was in development (as they were trying to sell to the halal market), and I’d say it does taste scarily close to the sisig my dad used to make—chewy, creamy, and sour. I do recommend you try the mix out if you can get your hands on it. No, I’m not getting paid by nor do I have any stake in Mama Sita’s to say this.

As I said, if I’m being pedantic. Frankly, I just see “sisig” as a lexical item to get the point across. If someone says they’re serving sisig, there’s a vague notion of what to expect. Something chopped. Maybe something sour. Maybe there’s a twist. I really am pedantic only upon request: again, as a Kapampangan, I get asked what I think about the dish I’m having. Only when I hear “Carlos, is this authentic enough?” then I’d have to go on this ramble about it. Well, now I could just send them the link to this post.

But there’s still much to be said.

Who benefits from food authenticity?

Tourism and economic impacts

The elephant in the room—tourism. Since cuisine is highly intertwined with culture, culinary tourism has a large impact in experiential travel as a whole. I mean, it’s just obvious: people gotta eat. Food not only sates appetites; food authenticity also draws tourists to an area. People go to Aling Lucing’s for sisig the same way people go to Japan for sushi. I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader to look for hard numbers supporting that claim.

The economic impact of culinary tourism is unmistakable. It’s in the best interest for people to develop a culinary identity through setting standards for authenticity to set clear cultural borders. To develop a sense of “heirloom” and “heritage” dishes, which attracts tourists both domestically and internationally.

In a sense, culinary tourism also transcends geographical ethnolinguistic borders. Diaspora can also benefit from food authenticity by setting up ethnic enclaves promoting said authentic dishes. Examples range from a bulaluhan in Italy, to small kebab shops in Pasay, to Chinatowns and Little Indias, to even Jollibees globally. While food being delicious is the primary draw, I’d argue food being authentic plays a significant role as well.

Note that these cultural pockets of authentic food serves not only tourists, but also expats. During my half-year stay in Korea, it was particularly difficult to find Filipino food where I was staying (KAIST in Daejeon). I’ll have to ask my friend but there was only one place we visited that served Filipino food using local ingredients (and imported sinigang mix). Pictured above4 is the Philippine food market in Daehangno which I also had the pleasure to visit in Seoul. On top of catering to culinary tourists (e.g. curious Koreans), this assists expats and migrants both economically and socially, providing income and a support system, respectively.

Gastronationalism and group identity

Intertwined with the point above, food authenticity also contributes to a sense of gastronationalism. Like language, place of birth, among others—cuisine definitely makes it easier to conform oneself to a sense of national identity. In the sea of complaints on “inauthenticity,” you’ll find that ethnic groups coalesce with less friction if there were standards in place for food authenticity.

Personally, it’s way easier to resonate with a cabalen when we’re talking about “authentic” food. This transcends distance—and is also partially diasporic. There is indeed a certain sense of belonging and collective identity when you both agree on the idiosyncrasies of Kapampangan tocino, and that sisig shouldn’t have egg or mayo on it.

This concept is only recently explored—you’ll find discourse on it mainly popping up in the 2000s. Later on, I’ll present a theory why this is so, but this idea is fairly new, and even my thoughts on it are not yet definitive.

While I have personal views on the concept of nationalism and the nation-state, I’ll defer those to a story for another time.

Should we seek the authentic?

Loss of personal identity in the name of tradition

Consistency in cooking a dish is valued in reputable restaurants—you wouldn’t want to go eat out at your favorite place and expect only 20% of the time for the food to be good. However, in home cooking, that’s a bit hard to come by. A home cook’s mood may change. The heat control is different every day. The quality and availability of ingredients are seasonal. There’s a lot of factors involved in cooking, hence why consistency is placed on a pedestal: a close second to how good a dish tastes.

However, even at times I find consistency quite monotonous—I wouldn’t eat the same dish at a Chili’s everyday, for both financial and gastronomical reasons. Which is why you have a freedom of choice: order something different, or order some sides. Go out for Mexican today, and maybe get Japanese tomorrow.

Home cooking is, in my opinion, a crucial skill everyone should have. You can cook Mexican today, and maybe Japanese tomorrow. Maybe you’d like to have a bit more cheese on your taco. Maybe you’d want your curry spicier. Maybe you’d like to have egg on your sisig. Cooking, just like any art, is a form of expression—a medium from soul to tastebud where you could show who you are, and what your story is.

While gastronationalism, even at a provincial level, improves cohesion and local tourism—I’d say it limits personal experimentation. Consequentially, this forces the home cook to rigidly adhere to a set of ingredients and procedures. It’s reductionist. My sisig is no longer my sisig. Social norms dictate it’s the “wrong sisig, made your way.” It’s honestly ridiculous.

As [Kapampangan scholar] Mike Pangilinan said, “For us Kapampángans, cooking is not a mere hobby or a past time. It is an essential part of our identity. It is an expression of who we are as a people. It is our soul. Therefore we get hurt and angry whenever somebody steals our soul and identity and calls it simply Filipino food rather than Kapampangan dish. Worse is when you twist it and play around with it to the point that we can no longer recognise ourselves in it.”1

Is that not revolting? I think for everyone, cooking is an essential part of one’s identity—why limit it to Kapampangans? Sure, historically, Kapampangans had an “edge” during Spanish rule, but I’d argue holding onto that pride is simply baseless today. Not only it stifles culinary innovation, the idea itself, I believe, is approached at a wrong angle: why couldn’t everyone enjoy cooking? One could even argue: “why call it a Kapampangan dish when it’s my dish?” While it’s good to be proud of your own heritage, it’s simply snobbery and elitism to ethnically monopolize it.

Additionally, saying someone “steals your soul” is unnecessarily tribalist and nonsensical. Where do you draw the line? While cultural appropriation is a contentious topic I’d love to get into, I don’t want to risk creeping the scope of this post.

Impacts of the internet and globalization

I’d argue that notions of food authenticity before the information age were more local. I doubt that, without the internet, people won’t be debating what “authentic” pasta carbonara5 was, unlike today. The spread of information via the internet, I believe, is a large amplifier of hardline thoughts on food authenticity today.

Diaspora may be complicit—but I’d argue largely harmless. There’s an inherent sense of being “present for each other,” where tolerance and empathy overtakes subethnic pride. Expats also rely on limited ingredients—shaoxing wine, fish sauce, and other relatively endemic ingredients may not be regularly available outside of Asia hence their (natural) tolerance to variation and innovation.

As mentioned in previous sections, gastronationalism seems to be a novel concept. While it does increase cohesion in many ways, it also brings about friction in other cases as well. Take for example xiaolongbao (or XLB, in Filipino slang). While marketed as largely Taiwanese by famous chain Din Tai Fung, its origin is still a highly controversial topic when talked about with the Shanghainese6.

In conclusion

Personally, no, we shouldn’t seek food authenticity. Rather than seeking authenticity, I find sharing known origin stories about food, in a non-condescending way, a more human experience rooted in empathy. Yes, we should talk about the history of a dish, but arguing how a dish is “correctly” made is quite unproductive. Innovation in food shouldn’t be stopped in the name of “preserving tradition”—if anything, it prevents the spread of culinary culture in places where the palate and the dish are less compatible.

In fact, I’d go even as far to say as every dish in the world is born from said innovation. Is stopping the synthesis of new culinary experiences worth preserving tradition? Are there other ways to preserve tradition? To an extreme: is tradition even worth preserving in the first place?

I’ve found that inflexibility brought about by food authenticity divides the world more than it unites it—and my personal philosophy simply just goes against that. Cuisine should be shared by everyone; whether it’s eating it, making it, or changing it.

Footnotes

-

Banal, R. (n.d.). Sisig with egg and Mayo? thanks, but kapampangans aren’t having any of that. GMA News Online. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/lifestyle/food/651699/sisig-with-egg-and-mayo-thanks-but-kapampangans-aren-t-having-any-of-that/story/ ↩ ↩2

-

While Bergaño, 1732, is often cited here, I don’t think I’m equipped to interpret 500+ pages of pre-Victorian Spanish text. Wikipedia text is also quite unreliable when it comes to historical Philippine (specifically, provincial) topics, so do take this with a grain of salr. ↩

-

The Wikipedia page for sisig, while citing some reliable sources, such as a 1700s dictionary, is mostly a propaganda page. Most of the 18 (at the time of writing) sources are links to Filipino news articles, the earliest being from 2007. The news articles themselves do not cite any written sources whatsoever, only interviews from (1) restaurant owners or (2) politicians. I find this quite disappointing and I do hope the page gets reworked soon. I believe this flies under the radar since the topic of sisig is rarely disputed by… academics who have more important stuff to look at. ↩

-

Sadly, I didn’t get to take photographs during my stay. Photo is taken from this article, which is also worth a read. ↩

-

Carbonara is also a contentious subject. I used to hold a view as well that “carbonara isn’t carbonara if XYZ ingredients weren’t used.” I recommend watching this video (timestamp linked) showing the origins of carbonara. Fun fact: the omission of cream was only a relatively recent trend, starting in the late 90s / early 2000s, even in Italy. ↩

-

I can’t talk much about this since (1) I’ve yet to do my due diligence and (2) definitively deciding about food origin is counter-productive to my points. If you’d like to read more: https://www.good.is/food/xiaolongbao-taiwan-shanghai ↩